Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales: final report - Chapter 3: strengthening Welsh democracy

Final report of the commission detailing options to strengthen Welsh democracy and deliver improvements for the people of Wales.

This file may not be fully accessible.

In this page

Introduction

This chapter tackles the second part of our remit - strengthening Welsh democracy. We propose an expansive view of democracy, with citizen engagement routinely embedded in politics and policy making. We argue for strengthening electoral democracy, making greater use of democratic innovations, with myriad opportunities for citizens to participate on the issues they care about.

Representative democracy under strain

In our interim report, we noted the international context of declining trust in democratic institutions and our intention to focus on ways of responding to this in Wales. The democratic process derives its legitimacy from the electoral process, but it involves much more than elections.

Despite the growing confidence and maturity of Wales’ democratic institutions during the two decades since devolution, there are weaknesses in the country’s democracy, not least in citizen engagement. Turnout at Senedd elections remains stubbornly low, but this is only a headline indicator of deeper issues. Several recent reports have highlighted the growing challenges facing Welsh democracy, including low levels of public knowledge of and engagement with Wales’ democratic institutions and “democratic backsliding” where democratic standards gradually decline over time (Defining, Measuring, and Monitoring Democratic Health in Wales, 2023 and Building Bridges: Wales’ Democracy – now, and for our future, 2023).

As set out in the previous chapter, one of the strongest arguments citizens made for constitutional change is that they feel that their votes, and their voices, do not have enough influence on the actions of government. This message came through from all the qualitative sources, including the citizens’ panels and the online survey responses. Citizens have told us that the power to vote is an inadequate mechanism for meaningful influence over decisions made in their name.

We noted in chapter 2 that many people conflate the actions of the government with the governance structures that it works within. This is a particular challenge in Wales, where the democratic institutions have been subject to repeated change, and there have been relatively long periods of Conservative-led government at Westminster and Labour-led government in Wales.

Strengthening trust and engagement with the process of government is the responsibility of the whole of civic society, not just the political parties and the media. All need to contribute to countering the cynicism that corrodes trust in politics and politicians and undermines democracy. The mechanisms we discuss below are ways of enriching democracy by giving elected members better information on the views and ideas of citizens, when they are enabled to participate and given reliable information to draw on.

Regaining citizens’ confidence in representative democracy

Senedd reform

The objective of the current proposals for Senedd reform is to strengthen its capacity to represent people in Wales and to scrutinise and hold the Welsh Government to account. The Senedd has previously legislated to expand the franchise to include 16 and 17-year-olds, to improve the electoral registration process and to enable innovation in the way in which citizens can vote, using the powers devolved by the Wales Act 2017.

As part of its Co-operation Agreement with Plaid Cymru, the Welsh Government has brought forward proposals to increase the size of the Senedd from 60 to 96 Members, for implementation in time for the 2026 election. This is to increase its capacity to discharge its existing responsibilities, and to enable it to take on additional ones as and when the devolution settlement is modified. We strongly welcome these proposals, which build on the work of the Expert Panel convened by the Llywydd in the previous Senedd term.

Electing 96 members requires new electoral arrangements. The proposed scheme will create 16 Senedd constituencies, each returning 6 members on a ‘closed list’ proportional system calculated using the d’Hondt formula. Voters will be asked to choose between lists of candidates nominated by the political parties. The 6 members returned from each constituency will closely reflect the levels of support gained by each party in that constituency, but voters will not have the opportunity to select individual candidates.

We welcome the steps to increase proportionality and capacity in the current proposals, and we strongly support plans to review the new system after the 2026 election. The proposals in the Senedd Cymru (Members and Elections) Bill would require a Senedd Committee to prepare and publish a report on the operation and effects of the Act, considering issues such as:

- the impacts of the new voting system on proportionality

- the introduction of multi-member constituencies

- the experience of closed lists

The method of electing our representatives is crucial. The proposed closed list method is an improvement on the current ‘mixed member system’, where in the constituency vote, voters choose between one candidate selected by each party and, in the regional vote, between closed lists selected by political parties. This will deliver greater proportionality but means that voters will no longer have a direct connection with their local MS. Voters will only be able to choose between lists put forward by political parties and individual independent candidates, should they stand for election; they will not be able to vote in favour of, for example, a candidate who has been ranked in a lower position than another by their party.

We see a good case for alternatives such as a Single Transferable Vote or an open list system, where voters can choose between named individuals representing parties or independent candidates as well as between political parties. We recognise that this can lead to internal rivalries between candidates from the same party, but we encourage the committee to consider these factors along with voters’ perceptions of fairness in the system as part of its review.

The Explanatory Memorandum for the Senedd Cymru (Members and Elections) Bill set out that the committee will be able to

consider any other Senedd reform issue that it considers relevant in the context of undertaking a review of the extent to which the elements of a healthy democracy are present in Wales, and may consider:

- the awareness and understanding of devolved Welsh government and elections

- an assessment of turnout levels and an exploration of proposals for how this may be increased

- support for members and parties to undertake their Senedd roles

- the infrastructure in place to support a strong Welsh democracy

We recommend the planned review of the Senedd reforms should be resourced to ensure a robust and evidence-based analysis of the impact of the changes, including from the perspective of the voter and of democratic accountability.

Access to the franchise

The Welsh and UK governments are pursuing different approaches to electoral reform and the franchise. The former has made it easier to vote in Welsh national and local elections, extended the franchise to citizens of other countries who have the right to reside in Wales, restricted the rights of UK citizens living abroad to vote, and extended votes to 16 and 17-year-olds.

The UK government has taken the opposite approach, restricting the voting rights of citizens of other countries, expanding those of British citizens overseas, and introducing a requirement for ID before voting in elections to the Westminster Parliament and for Police and Crime Commissioners. The Electoral Commission has noted that the latter change was not based on evidence of fraud and many commentators have argued that it reflects an attempt at voter suppression.

We welcome the Welsh Government’s policy of maximising the participation of electors who pay taxes in Wales and making it easier for people to cast their vote. The different approaches mean that voters in Wales will participate in elections operating under different rules, with Senedd and local government elections operating under the Welsh Government approach, and elections to the Westminster Parliament and for Police and Crime Commissioners operating under UK government rules. This is confusing for voters, but in our view is a better outcome than extending the restrictive UK government model to devolved elections.

Democratic literacy

A strong message from our engagement is that citizens feel that they lack knowledge and understanding about how government systems work, who is responsible for what and how they can influence the political agenda.

Wales in the media

Citizens have told us that they do not get enough information through the media about what is happening in Wales. In the representative survey conducted for us by Beaufort Research, 73% of respondents agreed that “You don’t see or hear enough about how Wales is run in the media”. This was highlighted during the pandemic; many citizens told us of their confusion surrounding lockdown rules, when broadcasters mistakenly presented English rules as applicable in other parts of the UK (this was observed in Community Engagement Fund Reports and in Dweud eich Dweud: Have your Say responses, which were carried out under the final covid restrictions).

This is important for democratic literacy as for many people in Wales, especially older people, TV broadcasting is their main source of news.

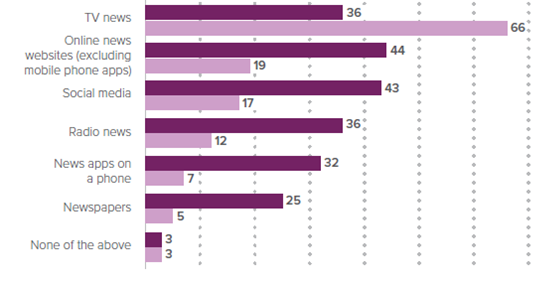

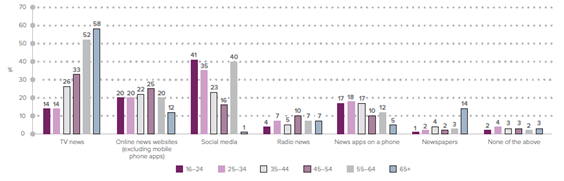

TV news is the main source of news and information generally for people in Wales, followed by online news websites and social media, but there are marked differences by age group.

Graph from the 2023 Beaufort Research report (Gathering public views on potential options for Wales’s constitutional future: Quantitative survey findings summary, Beaufort Research, 2023)

Graph from the 2023 Beaufort Research report (Gathering public views on potential options for Wales’s constitutional future: Quantitative survey findings summary, Beaufort Research, 2023)

Younger people are more likely to access news and information online, via websites, news apps and social media (Gathering public views on potential options for Wales’s constitutional future: Quantitative survey findings summary, Beaufort Research, 2023). These digital sources can be connected to traditional broadcast media; almost all news channels and newspapers have social media presence and dedicated apps.

If these sources do not accurately inform citizens of what is happening in Wales, and the actions that the government is taking in their names, then citizens will not be able to take well-informed decisions.

Enhancing democratic literacy in Wales

The response to the low levels of democratic literacy in Wales must include giving people more and better information about how democratic government works.

However, it must go further than simply information provision: people need the critical thinking skills to make sense of such information from a range of sources in the age of disinformation, social media, and polarised political views. The new Welsh curriculum is designed to strengthen the focus on these skills in schools, but a much wider reach is needed.

Participation in democratic processes, through political parties and trade unions, has an important part to play, as does involvement in campaigns and voluntary activities locally and nationally.

Democratic innovation

Adjusting the institutions and operation of representative democracy, such as reforming the electoral system, is one way of tackling the weaknesses of Welsh democracy. Another way involves introducing innovative mechanisms for including citizens in decision-making processes, as a way of reinvigorating democracy. Such mechanisms are often introduced alongside, and aim to complement, existing structures for electing politicians and governments. Through a focus on enhancing the participation of diverse social groups in democracy, and promoting informed, reasoned, and respectful deliberation between citizens, these innovations offer the potential for a more legitimate and effective form of democracy.

Local and central governments in many countries are using participative and deliberative mechanisms to support the work of democratic institutions and give citizens’ practical experience of debate and compromise. None of these are silver bullets but used judiciously they can have a significant effect on how citizens and elected representatives understand democracy and share power.

Participative and deliberative democracy

These terms are sometimes used interchangeably, and there is much overlap between the two. Neither approach is superior, both have value in enabling greater involvement of citizens in public life, alongside more conventional engagement mechanisms and traditional representative democracy.

‘Participatory democracy’ approaches are broadly concerned with involving citizens in active and meaningful ways in decisions that affect their lives (Public participation for 21st century democracy, 2015). Within these, ‘deliberative democracy’ approaches are typically more structured processes aimed at giving citizens information about a topic, and then supporting reflection and discussion in order to arrive at informed viewpoints (Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave, 2020). Both terms nevertheless encompass a huge variety of practices aimed at increasing citizens’ participation and deliberation in democracy.

The term ‘democratic innovations’ is often used to describe different participatory and deliberative formats. Democratic innovations are “processes or institutions developed to reimagine and deepen the role of citizens in democratic governance by increasing opportunities for participation, deliberation and influence” (Defining and typologising democratic innovations, 2019, p11). In practice, democratic innovations assume a wide range of forms (ibid, p25).

Examples of democratic innovations:

- Mini-publics (such as climate assemblies or citizens’ juries)

- Participatory budgeting

- Collaborative governance (such as community anchor organisations, Community Wealth-Building, or public-community partnerships)

- Ballots and citizen initiatives

- Digital crowdsourcing

Strengths and weaknesses

Advocates of democratic innovations argue that, when done well, these can lead to better policies and policy outcomes. They can enable policymakers to make hard policy choices, contribute to citizens becoming more informed, and restore citizens’ trust in the democratic political process.

However, there is also a rapidly growing body of evidence from across the world – based on evaluation of the design, implementation and outcomes of a diverse range of democratic innovations – of the limitations of these approaches. It was beyond the Commission’s scope to fully review this work, but the key challenges identified relate to recruitment to such democratic innovations, how they are organised and the extent to which they result in any policy or political change. The international experts that we spoke to nevertheless drew on this evidence base to outline three components of ‘what works’ in any participatory and deliberative process.

Democratic Innovations should be:

- multi-modal: combining a range of democratic innovations

- inclusive and deliberative

- empowered and consequential

(Taken from a presentation given to the Commission by Prof. Oliver Escobar, Professor of Public Policy and Democratic Innovation, Edinburgh University, 2023)

To be effective, these innovations must be central to the policy making process. There needs to be a clear connection to the decision-making process; if there is not enough political will to follow through on these processes, or if the outcomes become subject to partisan wrangling, this can increase disaffection and cynicism.

Democratic innovations can be resource intensive, so they should be introduced carefully and with clarity on how they will be used. In the UK such approaches have often been small, one-off pilots lacking sufficient connection to the political decision-making process to have meaningful long-term impact.

Moreover, such approaches should be used selectively, as not every democratic innovation will be suitable for all issues. There can be an alienating effect if governments over-promise and under-deliver in responding to the outcomes of significant time invested by citizens.

Processes should be tailored to the local communities involved. Much care is needed to design processes that are meaningful, impactful and representative, and include those who face barriers to participation. Democratic innovations across the world demonstrate the opportunities and challenges of gathering a truly representative body of citizens.

The Welsh experience

In Wales, there has also been growing interest in the potential of democratic innovations for engaging citizens with democratic processes and decision-making. This principle is central, for example, to the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act 2015, where one of the 5 ‘ways of working’ is “involvement”, with the aim of ensuring that public bodies in Wales involve people with an interest in achieving the well-being goals set out in the Act (Well-being of future generations act: the essentials). However, there is, as yet, no comparative data on how public bodies have implemented this principle in practice, and the extent to which the Act is driving a fundamental transformation of citizen engagement practices in Wales remains unclear.

There is nevertheless evidence of increased efforts across Wales to use different participatory and deliberative democracy approaches. We heard evidence, for example, of co-production strategies for enhancing citizens’ voice in developing social care and support plans, whilst the ‘Measuring the Mountain’ project convened a citizens’ jury to deliberate on what matters in social care to individuals in Wales. The Senedd, then known as the National Assembly for Wales, organised a citizens’ assembly in July 2019 to consider how people in Wales can shape their future through the work of the parliament, whilst in March 2021 the Blaenau Gwent Climate Assembly considered ways of tackling the climate crisis. The Institute of Welsh Affairs has also engaged a citizens’ panel to examine the role of the media in Wales.

Participatory budgeting has also been trialed in different places: it was used by the Police and Crime Commissioner in North Wales to allow community groups in Wrexham and Flintshire to allocate a proportion of money seized from criminals (Participatory Budgeting: an evidence review, 2017), whilst in Newport participatory budgeting is becoming normalised as a process of resource allocation to community wellbeing projects. We also received evidence of pilot projects across Wales that are developing creative approaches to deliberation, and which demonstrate the potential for Wales to innovate in this sphere and inform strategies for citizen engagement beyond Wales (Creative approaches to deliberation, 2023).

Despite these initiatives, the Welsh experience of participatory and deliberative democracy remains relatively limited and ad hoc. Some projects, such as that for improving the citizens’ voice in social care, have been impacted by austerity, the UK’s exit from the EU and then the global pandemic. The evaluation of the project so far found a significant gap between Welsh Government aspirations for transforming citizen engagement and actual achievements to date (taken from a presentation by Welsh Government officials to the commission in June 2023).

Other initiatives, like citizens’ assemblies, were only designed as one-off events with no clear route for influencing policy-making or political debate more broadly. The projects developing new creative methodologies for deliberation remain at a very small scale. Whilst promising in terms of their capacity to generate more inclusive and reflective deliberative conversations, they lack funding to be scaled up and to further explore how to link them to decision-makers at local, regional or national scales.

There is potential for public bodies in Wales to do much better than they have so far, to use innovative mechanisms to strengthen democracy in Wales.

A “constitution” for Wales?

The UK does not have a written constitution, nor do its constituent nations. The devolution settlement already contains some components of a written constitution, for example, the definition of powers in Schedule 7 to the Government of Wales Act 2006, the statutory partnership provisions in the Wales Act 1998, and the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act 2015. Moreover, the Government of Wales Act 2006 established the Senedd and the Welsh Ministers, delineated their powers, and set their rules of operation and the relationship between them.

Given the interaction with Westminster legislation which authorises the existence of the devolved institutions (most of which cannot be amended by the Senedd), it would not be possible to create a self-standing and comprehensive constitution for Wales under a devolved governance structure. However, drawing on these statutory examples and amplifying them with some general principles of good governance to produce a declaratory statement about how Wales is and should be governed could be a valuable step. If done by involving the citizens of Wales, this could provoke debate and reflection and enhance democratic and civic literacy in Wales.

Consulting widely on drafts and deploying deliberative and participatory democracy mechanisms would be an important way of bringing citizens into the process and giving the ‘constitution’ significance. This declaratory statement would need to be ratified by the Senedd, and its existence used to inform public understanding of governance in Wales. We believe that the production of a ‘made-in-Wales’ declaratory statement about our governance could have value in clarifying what the citizens of Wales want and expect from their governing institutions.

On this basis, we recommend that, drawing on the capacity and the expertise we recommend creating, the Welsh Government should lead a project to engage citizens in drafting a statement of constitutional and governance principles for Wales. Several countries have undertaken similar exercises, including Australia, Iceland, Egypt and Chile, while others such as Ireland and Canada have used democratic innovations on aspects of constitutional reform. These projects have had varying degrees of success; in undertaking such a project the Welsh Government should draw on the international experience of what works and what does not (How to Have a National Conversation on Wales’s Constitutional Future, 2023).

Subsidiarity and local government

We discuss how the different options for the future compare in terms of subsidiarity in chapter 7. In addition, we believe there is scope to extend subsidiarity within the current devolution settlement.

The principle of subsidiarity is that decisions are made at the level closest to the citizen, consistent with effective delivery. This involves a balance between economies of scale, local control, and accountability. Compared with its neighbours in Europe, the UK is a centralised state, with fewer powers held at regional or local government level than in many other similar sized nations.

Some argue that the Welsh Government holds too many responsibilities that could be delegated to local authorities or to regional groups of authorities. Proposals to enhance subsidiarity in this way depend on the capacity of authorities to take on new responsibilities. Many commentators argue that 22 local authorities in a country the size of Wales is too many. Since 1999, the Welsh Government has tried without success to reduce the number, including an option for voluntary merger of neighbouring authorities (which no local authority has taken up). Those who oppose change cite the cost of reorganisation, and the scope for disruption to services on which people rely.

Other factors militating against reform include:

- the limited funding available in the context of austerity, and relative increase in hypothecated funds, albeit that the Welsh Government has a Programme for Government commitment to reduce the number of specific grants, giving more control over spending to local authorities.

- pressure from voters and Members of the Senedd for the Welsh Ministers to have oversight, control, or intervention powers on local issues, so that Welsh Ministers can be held accountable for those issues.

- Welsh Ministers wanting to influence delivery more directly, and centralising services to make efficiency savings.

- A general centralising culture in political life across the UK, meaning decentralisation involves actively working against the way things have been done before and are done elsewhere in the UK.

Against this background, Welsh Ministers have legislated to strengthen regional collaboration between authorities and to strengthen local democracy by, for example, better remuneration for councillors and improved scrutiny mechanisms.

We met the Welsh Local Government Association on 2 occasions and considered their localism manifesto. Beyond this, we did not take evidence on the powers of local government, as we felt that this was beyond our remit.

Local government is a vitally important part of Welsh democracy, and local councillors have a very direct mandate and accountability within their area. We believe that their role should be part of the constitutional debate, and that elected members should engage constructively with the issues of scale and capacity mentioned above. The aim should be to achieve greater devolution within Wales as scale and capacity allows, and the Welsh Government, local authorities and other partners should work together on tackling these.

Conclusions

Our understanding of democracy should be more expansive than just a system of governance. Power as the capacity to make change is enhanced by distributed leadership which includes elected representatives and citizens. We need to complement and enrich representative democracy with deliberative and participatory mechanisms.

We encourage elected representatives to reflect on how democratic innovation can enhance the relevance of representative democracy and the quality of decision-making in Wales.

We make 3 recommendations to strengthen Welsh democracy. These initiatives are important, whatever constitutional model is ultimately supported by the people of Wales.

Recommendations

1. Democratic innovation

The Welsh Government should strengthen the capacity for democratic innovation and inclusive community engagement in Wales. This should draw on an expert advisory panel, and should be designed in partnership with the Senedd, local government and other partners. New strategies for civic education should be a priority for this work, which should be subject to regular review by the Senedd.

2. Constitutional principles

Drawing on this expertise, the Welsh Government should lead a project to engage citizens in drafting a statement of constitutional and governance principles for Wales.

3. Senedd reform

We recommend that the planned review of the Senedd reforms should be resourced to ensure a robust and evidence-based analysis of the impact of the changes, including from the perspectives of the voter and of democratic accountability.