Tax policy framework

The Welsh tax policy framework sets out the Welsh Government’s general approach to taxation, its strategic objectives and key challenges.

This file may not be fully accessible.

In this page

Foreword

Taxes are the admission charge we pay to live in a civilised society. They are the investment we make as citizens and as businesses for the public services we provide and enjoy collectively - from our roads and bridges to hospitals and schools, paying for the people who deliver these services and infrastructure, equipment and material resources they require. Taxes enable the people of Wales to achieve together the things we cannot manage alone.

Taxes help us create our own future. The public services we enjoy today owe much to the taxes raised in the past by our parents and grandparents. Continuing investment in our public services benefits not only ourselves but also the generations that will follow. Failure to invest now can result in missed opportunities and higher costs of investment in the future.

Taxes promote efficiency in the use of public funds, democratic accountability and incentivise governments to develop their economic and revenue base.

Taxes can influence behaviours - for good or bad - and they impose a cost on those who pay. The aim of government must therefore be to design tax policy in the most efficient and effective way possible, to bring maximum benefits at minimum cost. The balance between investment in public services, the competitiveness of the Welsh economy and the impact on tax payers will be at the forefront in our decisions, just as we use taxes as a lever to advance fairness and equality, enabling us to act together to tackle social issues, including justice and economic security.

Devolved tax policies should be aligned with existing Welsh Government policy objectives, efficiently operated and effective, and shaped by the following principles:

Welsh taxes should:

- Raise revenue to fund public services as fairly as possible

- Deliver Welsh Government policy objectives, in particular supporting jobs and growth

- Be clear, stable and simple

- Be developed through collaboration and involvement

- Contribute directly to the Well Being of Future Generations Act goal of creating a more equal Wales.

Each tax should have a defined purpose and be flexibly designed to link together where appropriate, in particular in the context of the wider UK and international tax system.

Wales has an opportunity to involve citizens and taxpayers in decisions about the levels and extent of revenue-raising, alongside decisions about spending, through debate and wider engagement. This should support continued development of relationships between citizens and Assembly Members, the National Assembly and the Welsh Government.

I believe that tax policy in Wales needs to be established and developed within a strategic framework. I intend that this framework should bring clarity and certainty to people in Wales, tax experts and professionals, businesses, and the wider public sector about our priorities for taxes in Wales, how we will engage with experts as well as taxpayers in the development of our tax policies, and how we will deliver a clear, stable, progressive and robust Welsh tax regime.

Mark Drakeford

Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Local Government

Introduction: devolution context

- Following the 2011 referendum, the National Assembly for Wales gained primary law-making powers in areas of devolved responsibility. However, since devolution to Wales in 1999, public services financed by the Welsh Government have been funded by a block grant from the UK government, while local services have been funded in part by council tax and non-domestic rates.

- The Welsh Government's funding arrangements have been the subject of considerable academic, public and political debate. In 2008, the Welsh Government established the Independent Commission on Funding and Finance for Wales (the Holtham Commission) to assess the operation of the existing approach to funding devolved public services in Wales, and to identify possible alternative mechanisms. In 2011, the UK government established the Commission on Devolution in Wales (the Silk Commission) to review the case for the devolution of fiscal powers and to recommend a package of powers to improve the financial accountability of the Assembly, consistent with the UK’s fiscal objectives (this formed the first part of the remit of the Commission on Devolution in Wales; In the second part of its work, the commission reviewed the non-financial powers of the National Assembly for Wales).

- The work of these independent commissions led to the Wales Act 2014, which devolved a range of new financial provisions to the National Assembly, including powers over taxation - specifically stamp duty land tax (SDLT); landfill tax (LfT); the partial devolution of income tax and the power to create new taxes in areas of devolved responsibility. Annex A summarises the scope of the Welsh Government’s devolved fiscal powers.

- The Wales Act 2017 removed the requirement for a referendum before the income tax powers could commence. Following agreement on the Fiscal Framework for Wales, the Welsh Government has committed to implementing Welsh rates of income tax from April 2019.

- As a result of these changes, the block grant will be reduced by an amount comparable to the forecast tax revenue, to reflect the fact that those revenues will go directly to the Welsh Government instead of the UK Exchequer.

- By April 2019, the new income tax powers, the replacements for SDLT and LfT (land transaction tax, LTT, and landfill disposals tax, LDT), together with council tax and non-domestic rates, will mean that around £5 billion of spending on Welsh public services will be funded by tax revenue collected and managed by Welsh central or local government.

- This will provide a powerful set of tax levers to support public spending. It will enable the Welsh Government to take a more strategic, integrated and long-term approach to tax policy, better to meet the needs of the people of Wales.

The challenges

Joined-up

- The Welsh Government will introduce LTT and LDT in April 2018, followed by Welsh rates of income tax in April 2019. During the development of LTT and LDT, stakeholders have made clear they should be consistent with existing arrangements as far as possible: Welsh taxpayers will continue to pay non-devolved taxes, and the devolved and partially-devolved taxes sit within a wider UK tax context, and within a wider international context.

- The devolution of tax powers provides a range of opportunities for the Welsh Government to develop a Welsh approach to taxation. There would be practical and policy challenges if the Welsh Government were to seek to remain consistent with arrangements elsewhere in the UK on an ongoing basis, given the frequency with which the UK Government adjusts taxes which are devolved in Wales - the devolution of tax powers to Scotland and Northern Ireland is also likely to lead to tax differences across the UK. The power to introduce new devolved taxes has generated new thinking about tax policy in Wales, providing a further tool to help achieve policy outcomes. Through this tax policy framework, we will be leading the debate in Wales and not simply responding to decisions made elsewhere.

- Taxes serve a variety of purposes and there should be flexibility for a range of levers to exist alongside each other, with different types of accountability (to local or national government) and funding mechanisms to local authorities, the Welsh Government or hypothecated to other causes, as with the carrier bag levy.

- Welsh households, businesses and organisations pay council tax and non-domestic rates as a contribution to the cost of delivering a wide range of services provided locally, by councils, police services, fire services, community councils and other public bodies. Net of reductions, this amounts to around £2.4 billion annually. The legislative framework within which council tax can be charged, collected and managed is set by the Welsh Government, but the level of tax itself is set by local authorities. Non-domestic rates are set nationally, pooled and reallocated to local authorities and police and crime commissioners. These tax streams form part of the local government finance system and can only be used to fund local government services.

- Implementing the new tax powers requires the development of a Welsh tax policy and strategic framework for taxation in Wales. It will be necessary to ensure that Welsh taxes support the Welsh Government’s policy and fiscal objectives, promoting fairness as well as supporting jobs and economic growth, in a wider UK and international context.

- The fully devolved taxes (LTT and LDT) will be collected and managed by the Welsh Revenue Authority, a new non-Ministerial Government Department which will partner the Welsh Treasury and support tax policy development within the Welsh Government. As a partially devolved tax, Welsh Rates of Income Tax will continue to be collected by HMRC, with the appropriate revenues being directed to the Welsh Government. There will be the continuing relationship between the Welsh Government and local government in relation to council tax and non-domestic rates. Taxpayers in Wales may be paying Welsh taxes to more than one Welsh organisation (i.e. the WRA and local authorities), and therefore more consideration will need to be given to how the right level of service is provided in a coordinated way.

New taxes

- The Wales Act 2014 provides a route for the Welsh Government to develop new taxes. This is a potentially powerful lever, but one which should be used with clarity about policy and fiscal objectives, and administrative efficiency.

Taxes and the economy

- From April 2018, the Welsh Government will be responsible for setting rates and bands for LTT and rates for LDT. From April 2019, it will set Welsh rates of income tax. In doing so, it will develop capacity and expertise in tax forecasting and the management of fiscal levers, such as the enhanced borrowing powers, to support budget decision making linked to policy objectives for the quality and quantity of public services and to deliver fair economic growth.

- Decisions over Welsh taxes will also have a direct impact on the Welsh economy as taxes represent a cost to tax payers. It is, therefore, important to consider the impact of taxation on the overall competitiveness of the Welsh economy and the balance between taxation and the level of investment in economic and social assets.

A framework for Welsh tax policy

- The Welsh Government's principles for tax policy in Wales have been set out. Taxation should raise revenue to fund public services as fairly as possible. It should help deliver wider fiscal and policy objectives, in particular supporting jobs and economic growth. It should be simple, clear, progressive and stable, with legislative and administrative clarity and efficiency. Given the core role of taxation in funding public services, it will be critical to engage with taxpayers about the general and specific elements of Welsh taxes.

- Tax policy in Wales needs to be established and developed within a strategic framework. This will bring clarity to stakeholders and will provide the basis for making the tax policy process as transparent as possible (Footnote 1). The Welsh tax policy framework will set the Welsh Government’s general approach to taxation, our strategic objectives and key challenges. The framework will also summarise the Welsh Government’s policy process for taxation in Wales, including the approach to engagement and publication.

- The objective of the tax policy framework is to make sure Wales has an effective, fair and efficient tax system, taking into account the following strategic matters.

Does Wales have the right level of devolved powers?

- Internationally, it is widely recognised that there is a general case in principle for the devolution of some tax powers from the central government in terms of promoting efficiency, democratic accountability of public spending and developing the economic and revenue base (annex B provides a summary of the evidence base). The exact range of powers varies considerably across countries and between levels of devolved and local government to reflect economic, social and wider political considerations.

- This line of reasoning, developed over a number of years and led by the work of the Holtham and Silk Commissions, has guided consideration of which fiscal powers should be devolved to Wales. The commissions, which gained cross-party support within the National Assembly for Wales, demonstrated the value of taking a considered approach to fiscal devolution within the UK.

- The commissions developed a framework for considering the case for devolved tax powers. The future shape of fiscal devolution should continue to be considered within that framework, to be able to assess robustly any new proposals should they arise. A central element is the role of the union - the UK. Wales positively contributes to the union and receives benefits in return. Fiscal devolution should be consistent with the principles of the political, economic and social union. Tax devolution should not undermine the integrated UK market for goods and services and should be consistent with the role that taxation plays in redistributing income within the UK.

- In addition, the frameworks from both the Holtham and Silk Commissions identified the role that an effective Welsh tax system has in enhancing the financial accountability of local and national government. To do this, Welsh taxes need to enable Welsh Ministers or local government, as appropriate, to offer citizens a choice between decisions over taxation and spending in a clear and transparent way. Devolved tax powers should also empower Welsh Ministers by enhancing the range of policy tools available.

- Within the UK, the extent to which devolved government has control over tax levers differs and this asymmetry has been shaped in part by the political preferences of citizens within each nation. With full implementation of the Wales Act 2014, the Welsh Government will be responsible for the devolved taxes, non-domestic rates and a share of income tax, meaning it will raise around 20% of its budget. These taxes, as a share of total taxes collected, put Wales broadly in line with the average level of sub-national tax responsibility across OECD countries, (see Annex B).

- It is important to recognise that the UK Government has yet to implement all the recommendations from the Silk Commission. The UK Government continues to deny Wales the flexibility to vary air passenger duty (APD) as is possible in Northern Ireland and Scotland. In relation to APD there is no case for treating Wales differently from the other devolved nations.

- Following the decision to leave the EU, some of the legal constraints to the devolution of existing UK taxes may change. Existing EU frameworks, such as for VAT, state aid issues and the aggregates levy, may no longer apply in the same way. This widens the issues for consideration, including the integrated border between Wales and England and the economic functioning of the union as a whole.

- Within Wales there continues to be a welcome debate about the scope of fiscal devolution, particularly in the context of fiscal devolution elsewhere across the UK. The range of devolved tax powers from April 2019 enables the political parties at National Assembly to offer people in Wales a choice about the level of taxes paid and the corresponding quality and quantity of devolved public services. It is absolutely critical that the existing scope and remit of tax devolution is maintained, as set out in the Government of Wales Act(s), associated Command Paper, relevant Welsh tax Act(s), and the fiscal framework for the Welsh Government. As the capability and capacity for managing those levers develops, there may be a case for further tax and fiscal devolution. However, these would need to be accompanied by a demonstration of how they could better deliver Welsh Government policy and fiscal objectives, enhance the accountability of elected representatives in Wales, and would also need widespread support within Wales.

What is the efficient overall level of taxation?

- One of the main purposes of taxation is to fund public services. With control of around £5 billion of tax revenues, devolved institutions in Wales can set the level of taxation which could increase or reduce the level of investment in public services. At a collective level, it will be important to seek to ensure the overall level of tax paid by individuals and businesses is assessed and the level of taxation is appropriate to the prevailing economic conditions. The Welsh Government has already committed to not increase income tax in this Assembly term, and will carefully consider tax rates and their impacts for the other Welsh taxes to ensure they continue to generate sufficient revenue to fund public services while remaining fair and supporting economic growth.

- In making decisions about individual taxes, we recognise the Welsh devolved taxes sit within a wider UK and international context. Welsh Ministers have acknowledged this, making clear there should be no change for change’s sake and recognising stakeholders’ interests in consistency.

- The economic, social and environmental wellbeing impacts of decisions about taxation in Wales must also be considered in the context of the Well Being of Future Generations Act (WBFGA). In particular, tax policy will be aligned with the WBFGA goal of creating a more equal Wales. The approach to tax policy and planning in Wales will embed the five ways of working: taking a long-term approach to seek to prevent problems before they occur, and working in an integrated and collaborative way, involving those who could be affected. While taxation funds the services individuals, communities and businesses benefit from, it is also a cost which can influence the behaviour and actions of taxpayers. When decisions about tax policy are announced, we will publish our assessment of the effect of those decisions on taxpayers, alongside statutory impact assessments.

What is the efficient balance and elements of taxation?

- There is scope for considering the balance of Welsh taxes: the relationship between the different Welsh taxes and the amount of revenue raised by each of them.

- International evidence shows that redistributing income and wealth through the tax system is a function typically reserved for central government (see Annex B). The Holtham and Silk Commissions recommended this should remain the case, and the Welsh Government agrees.

- While overall responsibility sits with the UK Government, the Welsh Government has levers to change the redistribution of income and wealth through the tax system to promote fairness and efficiency. Commitment to a progressive tax policy will be a central tenet of the Welsh Government’s approach to fiscal responsibilities. An effective tax system needs to recognise the contribution that Welsh taxes - as a whole - will have in the redistribution of income across households in Wales (Footnote 2). This will be a longer-term issue, assessing how the collection of taxes managed in Wales can better and more fairly meet the needs of taxpayers and public services, whilst supporting resilient local communities and services. The Welsh Government has already committed to ensure the council tax system is fairer - this is a priority area of work within the tax policy framework.

- The Welsh Government will look at the Welsh tax system as a whole and in the context of the UK system, to consider the impact of changes on households and individuals in Wales. The Welsh Government is committed to developing a fairer society in Wales, and will use the tax system to promote fairness and economic growth.

- The Wales Act 2014 enables the Welsh Government to introduce new taxes in areas of devolved responsibility subject to approval from the National Assembly for Wales and both Houses of Parliament. Taxation can be used in conjunction with other measures to bring about behavioural change – to either discourage activity that imposes negative social impacts or to encourage activities that generate positive social benefits.

- Any new Welsh taxes will need to be consistent with the overall framework for fiscal devolution to Wales, which applied to the current set of Welsh taxes. The Command Paper published alongside the Wales Bill in 2014 outlines the framework in the context of new taxes. The ability to create new taxes is an important new policy lever and has stimulated some innovative thinking in Wales (Footnote 3).

- There is a role for taxation in influencing behaviour and the Welsh Government will consider whether new Welsh taxes could be introduced in an efficient way to operate alongside existing or new policy tools.

- One of the founding principles for the devolution of tax powers is to enable the Welsh Government to set taxes which better meet the needs and priorities of its citizens and taxpayers. Through devolution, there is the opportunity to tailor Welsh taxes in a way that better reflects the characteristics of the tax base in Wales.

- It is recognised that the devolution of powers over taxation is a significant change and the new arrangements will need time to become established. The immediate priority is the safe running of the current tax system, as capacity and capability is developed in new areas of responsibility. That is not to say the Welsh Government will not make changes to Welsh taxes - we have already revised the replacements for stamp duty land tax and landfill tax to make those taxes more appropriate for circumstances in Wales.

- The Welsh Government will continue to review Welsh taxes in the context of our legislative powers to ensure they are aligned to our priorities. We will continue to speak to stakeholders and taxpayers to make sure that Welsh taxes meet the needs of taxpayers. Viewing Welsh taxes through the eyes of the citizen will be a cornerstone of Welsh tax policy, important to both the administration of Welsh taxes and the development of policy.

How can we promote best practice in service delivery for Welsh taxpayers?

- The Welsh Revenue Authority (WRA) will collect and manage LTT and LDT from April 2018. It will pay the revenues into the Welsh Consolidated Fund to support public services in Wales. As part of this role, the WRA will help taxpayers pay the right amount of tax at the right time, but will take a robust approach to non-compliance. The WRA will have a data management role in order to deliver its own collection and management functions, and is legally required to protect this information at the same level as the other UK tax authorities (HMRC and Revenue Scotland).

- The WRA will work in partnership with the Welsh Treasury to support the Welsh Government’s wider policy development role in relation to tax strategy and policy, and will ensure proposals are operationally deliverable. The WRA will continue to work closely with tax experts and professionals to ensure the approach to tax collection and management is simple and clear.

- The WRA will need to publish statistical data in line with National Statistics responsibilities. In addition, the ability to publish and display data, in particular the use of maps to aid visual presentation, could help support wider democratic participation and policy development in Wales. The new possibilities offered by the devolution of tax administration will allow for integrated approaches to data and an enhanced focus on communicating clearly.

- Devolution presents the opportunity to focus more on the needs and preferences of citizens in Wales. The Welsh Government expects the WRA to work in partnership with local authorities and other UK tax authorities, to build a more comprehensive picture of the delivery of tax services, of compliance and of tax policy development, and to join up activity, where possible, for the benefit of taxpayers.

A tax policy process

- Early each calendar year, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Local Government will make a statement about the priorities for tax policy reform in Wales. These will reflect the Cabinet’s principles for Welsh taxes:

- Revenue raising to fund public services – Devolved tax receipts fund devolved public and local services in Wales. It is important to understand the revenues raised and the possible fiscal risks associated with the tax.

- Delivery of policy objectives, in particular to encourage jobs and economic growth – Welsh taxes should be fair, and support the wider policy objectives of the Welsh Government. Supporting jobs and growth will in turn help to tackle poverty. The approach to policy effectiveness should be set out in terms of the Well Being of Future Generations Act ways of working. The case for using taxation should be assessed against other ways to achieve the policy aim – for example regulation or guidance - and should only be implemented if it is deemed more proportionate and effective than alternative policy tools.

- Simple, clear and stable – We will consider the administrative burden for taxpayers and the wider economic impact of the tax, and will seek to minimise these. A Welsh tax should not impose disproportionately high costs of collecting the revenue, including the cost of dealing with tax avoidance and evasion.

- Collaboration and involvement - Any proposals to change tax will be informed by a full assessment of the priorities and needs of key stakeholders, including taxpayers, businesses, tax professionals and other experts.

- Creating a more equal Wales – Tax policy will contribute directly to the Well Being of Future Generations Act goal.

- There will be trade-offs between the criteria, so any new tax or reform of existing taxes needs to be carefully considered using the available evidence base.

- The Welsh Government will establish a tax policy process to ensure that tax-related proposals are considered robustly and in line with the Cabinet’s principles. The process will also promote clarity and transparency about the approach to tax reform, and provide opportunities for engagement with tax professionals, taxpayers, and other interested groups. As decisions about tax policy will help determine the level of resources available to fund public services in Wales, the approach to tax policy will be aligned with the Welsh Government’s annual budget cycle.

- To ensure we meet the needs of people in Wales, build consensus and support, tax policy will be supported proactively with engagement with the National Assembly for Wales, stakeholders, tax practitioners and the public. Engagement will be facilitated though the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and Local Government’s Tax Advisory Group and the WRA’s Tax Forum and we will explore all opportunities to develop our thinking, including UK and international good practice.

- Taxation data and analysis will be published to foster understanding, and share knowledge and resources.

Annex A: the scope of Welsh Government fiscal levers

- The National Assembly for Wales has legislative competence in relation to local government finance. This includes most aspects of the council tax and non-domestic rates systems as they apply in Wales. The extent to which these taxes affect the resources available for devolved spending has been largely limited to decisions about the council tax system. Until 2015, non-domestic rates were managed within the Welsh Departmental Expenditure Limit and on a basis of equivalence with arrangements in England. The Welsh Government and UK government agreed to the financial devolution of non-domestic rates with effect from April 2015 (the financial devolution of non-domestic rates did not require primary legislation and therefore was not included in the Wales Act 2014).

- Through the Wales Act 2014, the National Assembly for Wales has the power to introduce a Welsh tax on transactions involving interests in land, a Welsh tax on disposals to landfill, and the power to introduce new taxes in areas of devolved responsibility subject to the agreement of both Houses of Parliament.

- The Wales Act 2014 includes provisions for the National Assembly for Wales to introduce Welsh rates of income tax to replace 10p worth of the existing UK rates. A requirement to hold a referendum to commence the income tax provisions was removed by the UK Government via the Wales Act 2017, and the Welsh Government has committed to introduce Welsh rates of income tax from April 2019. Each year, the prevailing UK income tax rates (basic, higher and additional) will be reduced by 10p for Welsh taxpayers (Footnote 4). The National Assembly for Wales will be required to pass a motion annually to set the Welsh rates of income tax which will apply. Different Welsh rates can be applied to each tax band but the National Assembly for Wales does not have powers to vary the income thresholds the rates apply to.

- The Wales Act 2014 provides the Welsh Government with revenue and capital borrowing powers. To help manage any fluctuations in the revenue stream from the devolved taxes, from April 2018 the Welsh Government can borrow up to £500 million (with an annual cap of £200 million), while a new Wales Reserve will help the Welsh Government manage resources across financial years. The Welsh Government can also borrow to invest in infrastructure, with the initial £500 million ceiling under the Wales Act 2014 doubled to £1 billion under the Wales Act 2017. The annual borrowing limit will be £125 million in 2018-19, rising to £150 million in 2019-20.

Annex B: The international context

- The Wales Act 2014 provides the current basis for fiscal devolution to Wales. However, it is important to consider the international evidence to draw lessons for Wales.

- The OECD (Fiscal Federalism 2014: making decentralisation work) states there is a general case in principle for the devolution of tax powers from central governments in terms of promoting efficiency, democratic accountability of public spending and enhanced incentives for developing the economic and revenue base. It further highlights the imbalance between spending and revenue decentralisation – across the OECD, around a third of government spending and two-thirds of public investment is carried out at the sub-central level, but only 15% of tax revenues go to this level of government. This is considered a barrier to sub-national accountability and a limiter of economic performance.

- The OECD also highlights the importance of fiscal equalisation and the role of a clear fiscal equalisation process alongside fiscal decentralisation. In the UK context, the fiscal union underpins the wider social and economic union and the decentralisation of fiscal powers should not weaken the fiscal equalisation within the union. The OECD argues the success of tax devolution is likely to depend on a wellfunctioning equalisation system. The current debate about fair funding and tax devolution, following the recommendation by the Silk Commission (Footnote 5) illustrates this in the Wales-UK context.

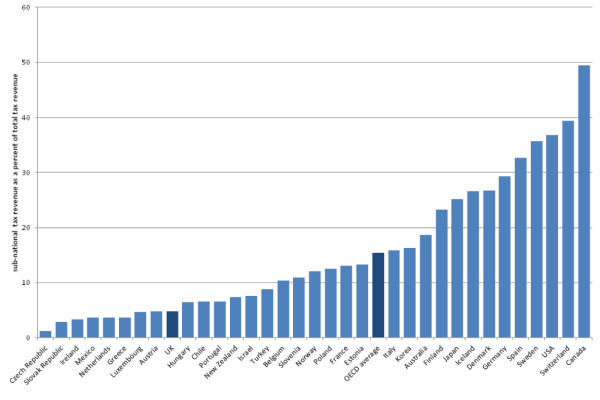

- There is a significant variation in spending and revenue decentralisation by country - for Canada, the US, Germany, Switzerland and Sweden - around 30% of all tax revenues are under the control of the sub-national government: but in Greece, the Czech Republic, Ireland and Mexico it is 3% or lower. Figure 1 summarises the per cent of tax revenue collected by the sub-national governments across OECD countries.

Figure 1: Sub-national tax revenue as a percentage of total tax revenue, 2011 (source: OECD Fiscal Decentralisation database)

- Across the OECD, there has been a general move to decentralisation of tax-raising powers. In 2011, the share of taxes (as a percentage of total tax revenue) collected at the local and state level had increased to 15.5%, from 13.5% in 1995 (OECD working papers about fiscal federalism; sub-central tax autonomy, 2011 update). By international standards, the UK has historically had one of the most centralised tax systems and yet has a high degree of decentralisation on the spending side - in 2011 the UK had decentralised 4.8% of tax revenue. However following the devolution of tax powers to the Devolved Administrations, the UK is following wider international trends of decentralisation.

- According to the OECD, it is typical for the central government to retain powers over the redistributive elements of taxes. There are also strong arguments in favour of the central government retaining taxes where revenues are highly sensitive to economic conditions as economic stabilisation is deemed a central government function. Recent events following the Eurozone crisis have highlighted the importance of clearly defined fiscal roles within the monetary union. As stated above, fiscal decentralisation in the UK should not undermine the fiscal, economic or social union. Reflecting the concerns regarding the scope for tax competition within national boundaries, the OECD also favours decentralisation of tax powers where the tax base is immobile. The OECD is clear about the need to avoid “negative sum tax games”.

- As a basic principle the OECD notes sub-national governments should rely on “benefit taxation” such as taxes that provide a link between taxes paid and public services provided. Within the UK, this has formed the basis of council tax whereby the tax partly funds the provision of local government services.

- Looking across the types of taxes that sub-national government typically have control over, taxation on individual’s income and property represents the largest share of sub-national tax revenues across the OECD. While sales taxes represent around 20 per cent of all sub-national revenue, sub-national government typically have limited autonomy over the setting of the tax. Typically sales taxes operate under tax sharing arrangements whereby the tax revenues are shared between the national and sub-national governments with no autonomy over the tax passed to the sub-national government. The international evidence suggests consumption/sales taxes are complex within highly-integrated economic entities, such as that between border areas of Wales and England.

- Sub-national governments are usually assigned greater levels of autonomy over property taxation than other forms of sub-national taxation. Between 1995 and 2011 there has been an increase in the share of sub-national revenues where the sub-national government has discretion over both the rates and the reliefs but a growing tendency for more central restrictions on the extent that sub-national government can change those rates and reliefs (OECD working papers about fiscal federalism; sub-central tax autonomy, 2011 update).

- Within the UK, the Mirrlees Review of tax policy identified 3 guiding principles for tax policy design. As far as possible the tax system should be neutral - they should treat similar activities in similar ways. A good tax system should be a simple one and a stable tax system is preferable to an unstable one. Fiscal decentralisation inevitably results in movement away from strict adherence to those guiding principles. While there are good reasons to do so, the decentralised fiscal model for Wales needs to remain coherent with the UK context.

- Reflecting the evidence base outlined above, property and personal income taxation represents the largest share of tax revenue at the subnational level of government. It is also the case that sub-national government tends to have greater autonomy over the rates and the design of taxes on property and land than any other tax.

- Both the Holtham and Silk Commissions based their recommendations on the international evidence. The new powers in the Wales Act 2014 for the partial devolution of income tax and the full devolution of stamp duty land tax and landfill tax reflect that evidence. While there is no correct level of tax decentralisation, the level of devolved responsibility puts Wales in line with the OECD average and be comparable with the situation in other countries, such as Finland and Italy.

- The Scotland Act 2016 includes provisions for the full devolution of income tax above the personal allowance, the assignment of VAT and the devolution of a range of welfare benefits. In England the UK Government has announced plans to localise non-domestic rates and proposals for the devolution of Attendance Allowance. There is a growing trend for further fiscal decentralisation within the UK.

- The command paper which accompanied the Wales Act 2014, recognises three routes by which the stock of Welsh taxes may increase, each of which requires the agreement of the National Assembly for Wales and both Houses of Parliament:

- The UK government may seek to devolve (in part or in full) an existing UK tax to Wales this would be subject to consultation with the Welsh Government

- The UK government may seek to devolve (in part or in full) a new UK tax that is aligned with areas of devolved responsibility, subject to consultation with the Welsh Government

- The Welsh Government may introduce new taxes, subject to meeting a range of criteria which would be set and assessed by HM Treasury.

- This document sets the framework for considering the case for further fiscal decentralisation in Wales.

Footnotes

[1] The OECD highlights the range of conditions which enable successful tax policy reform (Brys, B. (2011), Making fundamental tax reform happen, OECD Taxation Working Papers, No.3, OECD Publishing). It states the importance of a clear strategic vision for tax policy, which establishes the basis for all future tax reform. Central to the vision is a set of clear objectives against which tax policy reforms are assessed and evaluated.

[2] Data published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show the average income of the richest 5th of UK households before taxes and benefits was 14 times greater than the poorest 5th. After taking into account taxes and benefits, the ratio between the average incomes of the top and the bottom 5th of households is reduced to 4 to 1: UK household income and wealth on ONS.GOV.UK.

[3] Bevan Foundation (2016) Taxes for Good: New Taxes for a Better Wales

Independent Commission on Local Government Finance Wales

'Economic strategy' plan to improve social care on bbc.co.uk

[4] In most cases, people who live in Wales for the majority of the tax year will meet the conditions for being a Welsh taxpayer. However a full definition is provided in the Wales Act 2014.

[5] Recommendation 18 from the first report of the Silk Commission stated that:

We recommend that the transfer of income tax powers to the Welsh Government should be conditional upon resolving the issue of fair funding in a way that is agreed by both the Welsh and UK governments.