Workforce Partnership Council report: workforce mobility within public services

What workforce mobility in Wales looks like within public services.

This file may not be fully accessible.

In this page

Introduction

1. The Workforce Partnership Council (WPC) has an ambition to influence and develop workforce mobility, to encourage cohesive and collective approaches that support the movement of the public service workforce amongst its partner organisations, with a focus on action to mitigate or offer alternatives to redundancy situations.

To undertake this the WPC is committed to:

- Understanding the mobility of the public sector workforce and how they move between organisations

- Reviewing and developing the mechanisms that aid staff mobility on a tripartite social partnership basis.

2. This report and the research exercise that was undertaken aim to contribute to this ambition, by developing our understanding of the current issues and encouraging a debate around action to support public service workforce mobility.

Scope

3. Research was undertaken to answer a number of questions, and seek validation, or not, on assumptions of workforce mobility that already exist to ascertain:

- The current picture of workforce mobility and understand its context within public services

- How and why employees move between organisations and identify and analyse the circumstances

- How the People Exchange Cymru (PEC) website is used and viewed by partners to consider how its functionality can be improved and present proposals for future developments.

4. The scope of the report extended to those who are currently engaged and are represented at the WPC, therefore:

- WPC trade union side

- Welsh Government

- WPC employers' side to include local government, NHS Wales, Welsh Government, Welsh Government sponsored bodies, fire and rescue services, national parks.

Methodology

5. The research was undertaken in social partnership utilising a qualitative study. A survey of WPC partners, Employers and Trade Unions, provided questions to explore the following key themes and concepts that were derived from the literature review and desk research:

- Movement of the workforce – enablers and barriers

- People Exchange Cymru

- Benefits and dis-benefits of workforce mobility

- Improvements and recommendations for workforce mobility.

6. Whilst the phraseology of the question were different for Employers and Trade Unions, all 4 key themes were captured. The mobility questions were distributed through the WPC partners’ existing networks: Wales TUC in its role as the secretariat of the WPC trade union side, Welsh Local Government Association, NHS employers, Welsh Government, the Devolved Sector Group, with written responses returned to the WPC Joint Secretariat.

7. To obtain a reasonable response rate and ensure that all sectors were provided with the opportunity to contribute; where responses had not been received within the timescales requested, organisations were reminded via email and provided with opportunity to answer the questions via telephone interviews. This offer was taken up by a number of organisations.

Engagement

Trade union engagement

8. Facilitated through TUC Wales, responses from GMB and Unison were received at a local level with reference to local government.

Employer engagement

9. Overall there were 53 public service organisations contacted through the Employers’ networks.

| Sector | Table of response rates per sector | Number of responses received | Percentage response rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh Government and Welsh Government sponsored bodies | 14 | 11 | 79% |

| NHS health boards and trusts | 11 | 10 | 90% |

| Fire and rescue services and national parks | 6 | 3 | 50% |

| Local government authorities | 22 | 15 | 68% |

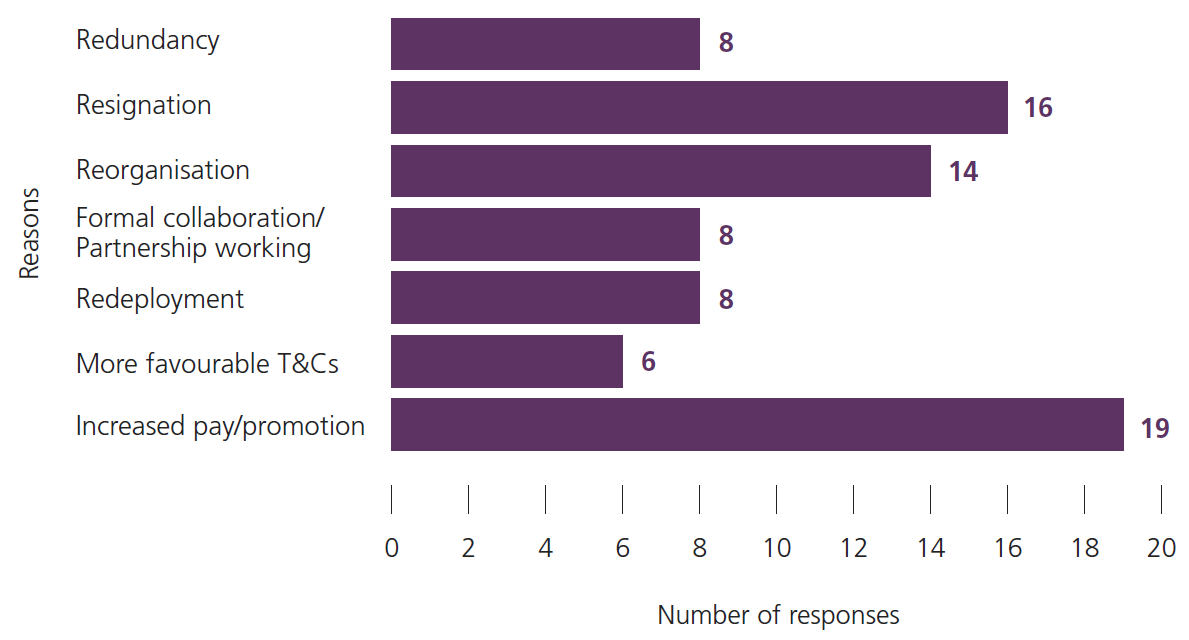

| Totals | 53 | 39 | 74% |

Welsh Government engagement

10. In addition to contributions from Welsh Government in its role as a public service employer, an investigation was also taken into Welsh Government policy and how current imperatives might drive an increase in the demand for workforce mobility across the devolved public services in Wales.

WPC Workforce Planning and Mobility Sub-Group

11. Until March 2018 the WPC, under its former arrangements, had a Workforce Planning and Mobility Sub-group which explored workforce mobility.

12. The work undertaken by the sub-group included a number of outputs linked to workforce mobility:

- Learning from the Greater Manchester Combined Authority which developed a collaborative protocol that sought to support the cross-public sector mobility of the workforce on a voluntary basis by recognising employees’ service, from other public sector employers. It is recognised the driver here is integration, the skills of the workforce and cost of redundancy.

- Pilot and develop of People Exchange Cymru where employment opportunities across public services in Wales are advertised.

- Workforce Mobility “Shared Risk” Model to share redundancy risks between employers.

13. Current work on workforce mobility, under the new WPC arrangements, including the findings within this report, seek to build upon the achievements of the Workforce Planning and Mobility Sub Group.

Literature review

14. A short review has been undertaken of key academic and public literature to better understand the concept of workforce mobility.

15. The focus of the literature is on a UK-basis and spans across the private sector and public services. However, there would appear to be a gap in relevant and current data at a Wales and public services level pertaining to workforce mobility.

16. To provide an informed basis for the study, this review examines: what is meant by workforce mobility, what are the causes and whether workforce mobility is a direct or indirect response to the causes, what impacts upon workforce mobility and what are the enablers and barriers.

17. The Institute for Fiscal Studies, June 2015 published research undertaken by Cribb and Sibieta, ‘Mobility of Private and Public Sector Workers’. This research is based on the Office for National Statistics’ data sets and mobility in this context is described as the flow of employment from and to the public and private sector over a number a years from 1998 to 2014, the report highlights that this is against the backdrop of austerity measures taken by central government. The findings reflect the rise and fall in workforce mobility as being directly linked to the UK’s economy and the movement of workers from non-productive roles to productive ones.

18. This research also outlines the impact of central government austerity measures in reducing the public sector workforce through involuntary (redundancy), or voluntary (employee choice) mobility. Involuntary and voluntary mobility in this context are described as movement of the workforce between the public sector and private sector depending on the transferability of skills. Cibb and Sibieta (2015) also identify that skills specific to the job or occupation are likely to contribute to lower levels of mobility, along with other factors such as the disparity of pay and pensions between the public and private sectors. The research determines that historically there have been higher levels of mobility within sectors, rather than across sectors.

19. Inter-sector transition has been examined by White (Inter-sector transitions: an exploration of the experiences of senior executives and managers who transitioned between the public, private, third and academic sectors 2017). The personal experiences of senior executives and managers who have transitioned between the public, private, third and academic sectors were explored. (Appendix 1 – Table Describing Enablers and Challenges to Inter-Sector Transitions, White (2017))The context is based on the blurring of organisational sectors due to the contribution of the private and third sector in delivering services and the concept of “boundaryless” working careers.

20. Caluwé et al (Mind-sets of boundaryless careers in the public sector: The vanguard of a more mobile workforce? 2014) describe a shift from “lifetime employment” to “lifetime employability” within the public sector; instead of offering a career for life, employees are expected to self-manage their own careers and therefore workforce mobility is increased through horizontal career movements or “boundaryless” careers. Caluwé (2014) cites that boundaryless careers are also in response to public organisations becoming flatter. The 4 types of mobility are identified based on physical and psychological movement, which highlights the importance of a “boundaryless mind-set”. (Appendix 2 – Illustration of Four Types of Mobility, Caluwé 2014)

21. In summary, the literature indicates that workforce mobility can be a response to a trigger, which in the case of Cibb and Sibieta (2015) was austerity. In these circumstances the mobility of the workforce is forced, due to the threat of redundancy. Conversely, where no threat of redundancy exists, the workforce can chose to move voluntarily, vertically, or horizontally within an organisation, or sector. Both Cibb and Sibieta (2015) and Caluwé (2014) identify transferable skills as a success factor for workforce mobility.

22. Those within the workforce that do undertake voluntary mobility, could also fall within the definition of embarking on a “boundaryless” career, which could be determined as an intuitive response by the employee to the triggers of flatter public services organisational structures and the demise of a job for life.

Data analysis

23. The responses were collated and the recurring themes from each question analysed in order to illustrate key findings for each social partner.

Trade unions

24. Views captured from the trade union were both at the local level in relation to local government and more broadly at the national level across public services.

25. When asked as to what prevents staff from moving between public service employers when faced with the risk of redundancy, different perspectives were provided by the trade union respondents within local government. One organisation was faced with instances of compulsory redundancy while the other was not. However, a lack of opportunities was cited as being a barrier to workforce mobility in conjunction with an ageing workforce and ambiguity on employer/employee expectations.

26. It was felt by the trade union respondents that there were no expectations for staff to seek other opportunities, or to be redeployed outside of their own organisation. Trade unions cited other difficulties including: an unfavourable view of employees on redeployment lists and differences in job evaluations for the same occupations across local government employers. An example of social workers was provided where employees would move between different authorities in order to seek higher pay.

27. The union respondents advised that other barriers included challenges linked to pensions, including the inability to port the Local Government Pension Scheme to other public service employers not on the modification order.

28. The cost of redundancy was also cited by unions as an issue, in that if an employee with continuous service was redeployed from one local government organisation to another, the redundancy liabilities would be passed to the new employer.

29. Factors enabling workforce mobility were described by unions as: redeployment and secondment policies, flexible retirement and communications with neighbouring Local Government Employers sharing vacancies, however this was noted as being ad hoc.

30. Reasons as to why employees were moving jobs were cited as being due to seeking increase pay and promotion, reorganisation and redeployment.

31. There was recognition that workforce mobility would become more important moving forward and whilst not all the trade unions were aware of People Exchange Cymru (PEC), the following suggestions were made to develop PEC and aid workforce mobility:

- Promoting the website and developing it as the integrated site where all opportunities are placed

- Link to, and increase staff training and upskilling including interview skills

- Provide employees with clarity on terms and conditions, pensions and continuous service to enable them to make informed choices

- Guaranteed interviews across public services where staff are at risk of redundancy

- Resolve the Local Government Pension Scheme Regulations to ensure equity with NHS Pensions and Civil Service Pension Scheme to enable an employee the right to be retained in the scheme if mobility occurs

- Provide automatic right of trade union recognition when employees move to another organisation where that trade union may not be prevalent.

Employers

32. In order to identify the current mechanisms in place that enable workforce mobility, and assess their effectiveness employers were asked to outline how movement of the workforce is enabled.

33. Feedback gained from employers identified that secondment opportunities were a significant aid to workforce mobility and to a lesser extent, so too was redeployment. Some respondents also identified that collaboration, regional working and partnership working also contributed to facilitating movement. Further information gained indicated that inward and outgoing secondments to organisations were usual.

34. The research suggests that public service employers are systematic in their approach to redundancy and the sourcing of reasonable alternative employment as part of the redeployment process within their own organisation.

35. It was found that redeployment is occurring, either as a consequence of reorganisation or as an alternative to redundancy. Further information gained from local government employers indicated that internal redeployment is common practice within individual organisations. One example from such an employer advised that redundancy monies were being redirected to retraining employees at risk in an attempt to secure ongoing employment within the organisation through redeployment. There was very little evidence to suggest that redeployments were secured across organisational boundaries within the same sector, regardless of the sector.

36. Within NHS Wales it was identified by employers that there were All Wales policies, such as an Organisational Change Policy through which redeployment is addressed and an All Wales Secondment Policy. There was little evidence to suggest that movement of employees occurred between NHS trusts and boards under these policies however one example of the Organisational Change policy in operation was provided, with redeployment occurring between neighbouring trusts on the basis of good working relationships.

37. The reasons received as to why workforce movement occurs was gained from employers and the key findings collated.

Why workforce mobility occurs: Employers' view

Reasons/Responses:

- Redundancy: 8

- Resignation: 16

- Reorganisation: 14

- Formal collaboration / partnership working: 8

- Redeployment: 8

- More favourable T&Cs: 6

- Increased payment/promotion: 19

38. Further discussions elicited the employers’ view that where redundancies were occurring it was commonly due to reorganisation, or as a result of fixed term contracts ending, either due to the cessation of funding or due to a task and finish assignment ending.

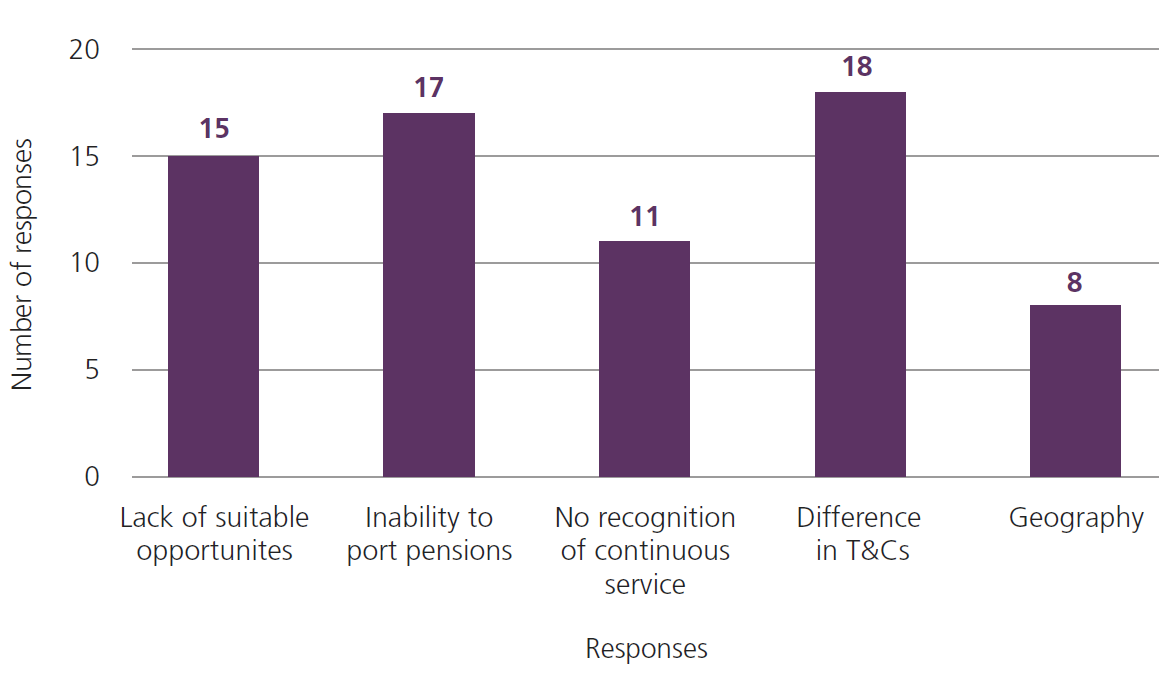

39. The employer respondents suggested that main barriers to workforce mobility within public services were:

Barriers to workforce mobility: Employers' view

Reasons / Responses:

- Lack of suitable opportunities: 15

- Inability to port pensions: 17

- No recognition of continuous service: 11

- Difference in T&Cs: 18

- Geography: 8

40. The impact of geography on workforce mobility was explained by employer respondents as:

- Rural locations: that rural locations offered limited employment opportunities, the only local employers are local government, the NHS or Welsh Government sponsored bodies; that employees often did not wish to travel beyond their local area for work (this was cited as being prevalent amongst low paid workers, or those with limited transport accessibility)

- Urban locations: where there are major transport links employee were able to be selective upon their choice of employer due to the ability to travel.

41. Additionally, a wide range of responses were received at a lower return rate from employers. These included:

- Lack of specialist skills and knowledge

- Lack of understanding of other public sectors

- Cost of VAT for secondments

- Inability to release staff on secondment due to own staff shortages

- Difficult to recruit and retain social workers

- Organisational/political priorities

- Cultural differences within the organisation/sectors

- Welsh language skills and inability to provide services through the medium of Welsh

42. Protection of continuous service is an important factor for consideration within each public sector body due to the bearing it has on calculations for statutory rights of employment e.g. statutory redundancy payment and statutory maternity pay. It is recognised that currently there is no mechanism for employees to carry over their accrued service from local government to the NHS and vice versa.

43. The portability of pensions and the ability for employees to continue to pay into the same scheme with a new employer/sector is also a challenge that is potentially hindering cross-public sector mobility of the workforce.

44. When asked about other influences that could affect workforce mobility, a wide range of responses were received from employers with the most frequent being around the differences between public services employers pay and grading structures. To a lesser extent Social Care was cited with reference to staff shortages, effects of the introduction of the Domiciliary Care Worker Registration, and the need to attract new employees into social care and the need to create a demand for employees to pursue a career in care.

45. Information was sought on the importance of workforce mobility in the current climate by employers providing a rating of 1-5, with 1 being not at all important and 5 being extremely important. The majority of responses indicated that the perception of employers was that it was currently “somewhat important”. However, there was also an indication that its importance would increase and that workforce mobility would be “very important” in the next 5 years.

46. Employers commented that the increasing importance of workforce mobility would be in response to the perceived future pressures on:

- Health and Social Care, this was cited by both NHS Wales and local government

- Budgets and the need to provide services with less resources, cited by local government and Welsh Government sponsored bodies (WGSBs)

- Skills shortages and hard to fill posts that are present today are predicted to continue in the future, cited by NHS Wales, local government and WGSBs.

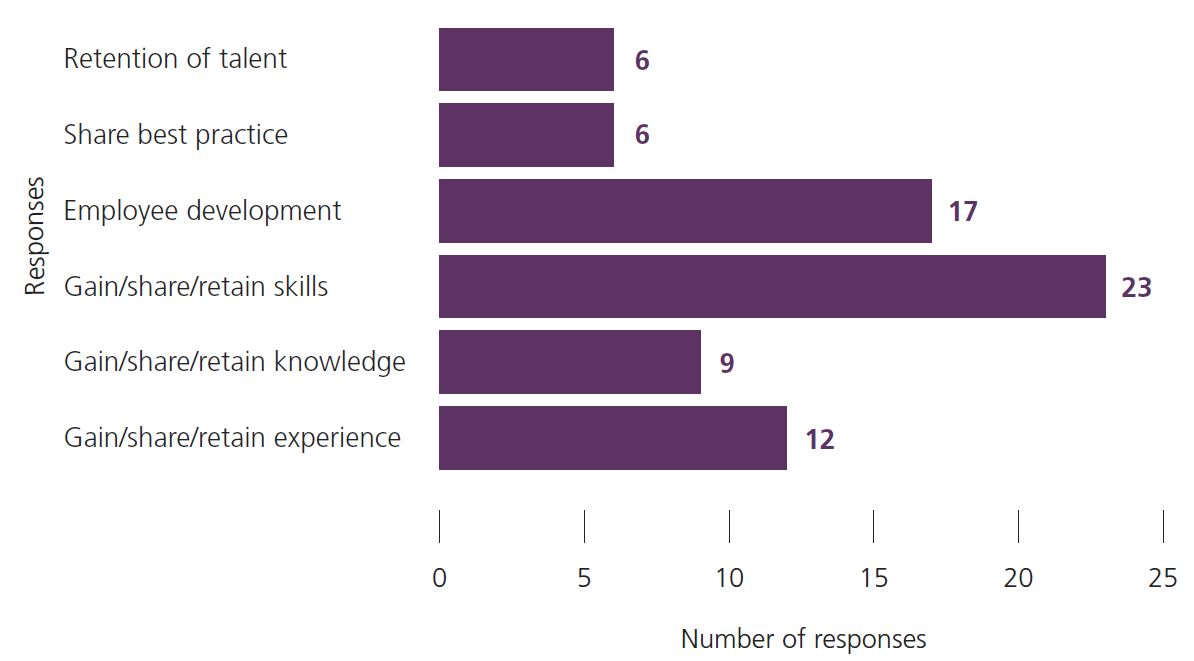

47. The responses to the benefits of workforce mobility indicates that there are mutual benefits to both employees and employers alike.

Benefits of workforce mobility: Employers' view

Reasons / Responses:

- Retention of talent: 6

- Share best practice: 6

- Employee development: 17

- Gain/share/retain skills: 23

- Gain/share/retain knowledge: 9

- Gain/share/retain experience: 12

48. When asked about the dis-benefits of workforce mobility, the employers’ responses to some extent endorsed the barriers to workforce mobility, but were varied and of low frequency.

Response / Frequency of response:

- Differences in Terms and Conditions: 9

- Loss of skills: 9

- Loss of knowledge: 5

- Cost of backfilling/recruitment: 5

- Lack of workforce stability: 5

- Loss of experience: 4

- Differences in pay and grading: 4

- Lack of recognition of continuous service: 3

- Inability to port pensions: 3

49. There was a positive response from employers when asked if workforce mobility should be improved between public service organisations. Similarly, when asked if workforce mobility should be improved between the public services and the private sector, there was a positive response but to a lesser extent.

50. An open question was asked of employers about what improvements could be made to facilitate workforce mobility. The top 5 frequent responses were:

Response / Frequency of response:

- Streamline Terms and Conditions: 8

- Promote public services (values, benefits, training, good news stories employee movement): 5

- Protect continuity of service: 5

- Enable pension portability: 4

- Recognition of transferable skills: 3

51. Local government employers’ suggestions on promoting public services included:

“Promote the type of organisation we are, its values, not just the salary. Promote the access to training and progression of apprenticeships” and “…attract people through promoting the added benefit of public service and contribution to the community.”

52. Information gathered from employers on the usage of People Exchange Cymru (PEC) confirmed:

- 20 respondents said they used PEC

- 10 respondents said they did not use PEC

- 2 respondents said they were not aware of PEC.

53. When asked from an employer’s perspective how the look and feel of PEC is rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being strongly disliked, and 5 being excellent the results did not provide a clear outcome. However, when asked if improvements or changes could be made to the site, suggestions included:

- 10 respondents proposed the need to improve functionality and usability of the site

- 6 respondents proposed PEC should link to the organisation’s own website

- 5 respondents proposed the need to raise the profile and generate greater awareness.

Welsh Government

54. A number of Welsh Government policies are focussed on joining up public services in order to improve services to citizens or improve efficiency. Mobility between sectors can help deliver this. Not all these policies and programmes will have direct or indirect implications for the relevant workforces or have links to workforce mobility. For example, co-location in the blue light services to share premises and promote collaboration between bodies does not always require staff mobility.

55. There is no specific policy statement or legislation from the Welsh Government on public service workforce mobility but some aspects of the current work programme should support mobility in practice. The Welsh Government has stated that it recognises the value to individuals of mobility across public sector organisations and that it takes an engaged, motivated and flexible workforce to deliver good services and to contribute to the wider wellbeing of Wales.

56. The Welsh Government’s Prosperity for All: the national strategy document sets out a broad range of areas of policy which may be relevant including areas which involve the co-location or integration of services.

57. One example is the Welsh Government’s plan for Health and Social Care, A Healthier Wales which outlines a community based approach in providing health and social care services outside of hospitals to help citizens stay healthy and independent. This calls for the NHS and social care to work together in the provision of high quality and potentially integrated services, which could drive an increase in workforce mobility.

Key findings

Recognition of the enablers and barriers in understanding the mobility for the public sector workforce

58. There is agreement between employers and trade unions that the current picture of workforce mobility is one where workforce mobility is being instigated on a voluntary basis by employees to seek increased pay and promotion and gain new skills and experience in different environments.

59. Where workforce mobility appears to be involuntary, both employers and trade unions share the view that it is due to reorganisation, securing redeployment, formal collaboration/partnership working arrangements or redundancy.

60. The research indicates that secondment and redeployment policies are in place and being utilised as key enablers to aid workforce mobility within the workplace.

61. The responses gained demonstrate that there are many benefits to workforce mobility; service development and improvement, individual career development, talent retention in public services, and both employers and trade unions agree that mobility should be improved between public service organisations.

62. There was also commonality between employers and trade unions on the barriers to workforce mobility which were suggested to be: the inability to port pensions, the differences in terms and conditions of employment amongst public service organisations and the lack of suitable opportunities.

Review of the mechanisms that aid staff mobility

63. A mechanism currently in place to facilitate public service workforce mobility is People Exchange Cymru (PEC), and according to the findings this is perhaps not effective as it could be due to the number of respondents that either did not use the website or were not aware of it.

64. From the research exercise it appears that there is no longer a demand for PEC to focus on addressing redundancy as a response to austerity, as was the case at its inception. Albeit that there remains fears of further budget cuts in local government and Welsh sponsored bodies.

65. In addressing PEC, a wide variety of suggestions were made by both employers and trade unions upon how it could be developed and become fit for purpose in the current climate. That is, how it can assist the increase in voluntary mobility for employees in gaining further skills, knowledge and experience for growth and development of their own careers.

66. Local government employers through the research have demonstrated that they are able to effectively redeploy employees at risk of redundancy within their own organisations and this is deemed to be business as usual.

67. Suggestions made by the employers and trade unions on what and how workforce mobility can be improved were wide ranging. These included promoting public services, recognising transferable skills and supporting voluntary movement to allow staff to expand their skills and experience. The range of responses received precluded any consensus but the suggestions could be further explored and evaluated with partners to determine whether any offer solutions to support the workforce mobility aims and ambitions of the WPC.

Appendix 1: Enablers and challenges to inter-sector transitions

Enablers of successful transitions

- familiarity with the destination sector prior to transitioning

- work values which align with those of the destination organisation

- appropriate professional skills

- mentoring support

Challenges to a successful transition

- organisational cultures

- the questioning of professional identity

- issues of self-esteem

Appendix 2: Illustration of 4 types of mobility

| Physical mobility (Perceived probability) | High | Low willingness, high probability Forced mindset |

High willingness, high probability Boundaryless mindset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Low willingness, low probability Sedentary mindset |

High willingness, low probability Bounded mindset |

|

| Low | High | ||

| Psychological mobility (Willingness) | |||