Public commemoration in Wales: guidance - Public commemoration in Wales: understanding the issues

Guidance for public bodies to reach well-informed decisions about existing and future public commemorations.

This file may not be fully accessible.

In this page

Part 1: understanding the issues

In both the past and present, people have created commemorations for a range of purposes. Generally, they have done so with honourable intentions; for example:

- to add to the character and quality of public spaces

- to contribute to local identity and place-making

- to express pride in an individual or achievement

- to respond to traumas such as persecution, conflicts or disasters

- to mark outstanding sacrifices; for example, lives given in rescues or defence

- to raise awareness of important historical events and places related to them

- to aid understanding and reconciliation.

Whatever the original intention, commemorations may have a damaging impact if they are felt to dominate places on behalf of particular individuals or groups. This could include the glorification of controversial individuals or the assertion of one interpretation of past events above others.

1.1: divisive commemoration and its impact

Workshop participant:

Commemorations are like bee stings – to me it could be just a bee sting, but to you it could be a horrific reaction.

Few public figures are viewed in the same way by everyone; some can be especially divisive. Politicians, in particular, are often controversial because of the impact of their policies on our daily lives, so people may react strongly for or against them. Similarly, military figures may be remembered by some for their bravery and sacrifice, and by others for the casualties of their campaigns.

The extent to which these different perceptions become an issue for communities depends on the depth of feeling and hurt. Most of us would not want to see commemorations put up that could trigger individuals to relive traumas they had experienced. People who have been subjected to racial prejudice or racist attacks may find it traumatic to see figures who had known connections to racist policies or actions, celebrated prominently.

Commemorations may have a particularly divisive impact in environments where there is no diversity of representation; for example, if in an ethnically mixed society people of only one heritage are acknowledged. Increasing the diversity of commemorations can therefore be an important way to reduce harm.

Commemorations that provoke division are damaging to social cohesion. But provoking thought, or challenging attitudes can be a positive response to contentious commemorations. It may be very important to commemorate an event such as a riot or a war that some might wish to forget. Likewise, it may be useful to commemorate major historical figures who were guilty of abuses if we can draw out lessons from the past through context and interpretation.

To note:

Decision-making needs to be sensitive to the ways in which commemorations may be perceived and the impact they may have right across society: diverse communities with different cultures, beliefs and views may be affected by public commemorations in different ways.

Case study: confederate statues as propaganda

Robert E. Lee (1807 to 1870) was an American plantation owner. During the civil war of 1861 to 1865, he led the forces of the Confederate States of America, which opposed the abolition of slavery. Long after the war, prominent public monuments were put up in southern states to Lee and other Confederate leaders, especially during the ‘Jim Crow’ era of racial segregation. The Lee monument in Charlottesville, Virginia, was installed in 1924 outside the public courthouse. In 2017 the city council voted to remove the statue after a violent rally, but this was delayed by legal challenges and protests involving white supremacists. The statue was defaced and finally moved to storage in 2021. Some 100 Confederate monuments have been removed since 2015 but 700 remain. Professor Ty Seidule of West Point Military Academy wrote in 2021 that the generation who built them had created ‘myths and lies’, which he and others had long believed, ‘to sustain a racial hierarchy dedicated to white political power reinforced by violence’.

1.2: the impact of type, style and symbolism in commemoration

Workshop participant:

I just want to say that whatever commemoration is done, they should do it mindfully, tastefully and truthfully.

Some commemorations are about individual people, often idealising them in statue form by putting them on a pedestal - literally. Such commemorations tend to present the subject in a positive light and ignore any negative aspects of their actions. In contrast, commemorations of events may simply recognise that the events took place rather than celebrate them. For example, Admiral Nelson on top of his column in Trafalgar Square in London is presented as a noble leader commanding the heart of the capital; however, the memorial to the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) in Portsmouth, which incorporates an anchor from Nelson’s ship, could be seen as a record of a historical fact.

1.2.1: plaques

Plaques may be less contentious than monuments because they could be understood to mark, rather than honour, an event or the association of a person with a place. Indeed, some plaques highlight negative aspects of the past, such as the existence of a prison, the location of a riot or the birthplace of a controversial figure. Most plaques carry only brief factual information such as a person’s name, dates, occupation and association with a place. Nevertheless, more elaborate examples might assert in text or imagery a view of a person or event that could be divisive. Plaques may also be contentious for leaving out important details about a person or event.

1.2.2: street and settlement names

Street names may seem to have less of an impact on the consciousness than other kinds of commemoration, but can nevertheless affirm problematic values and associations. These may be less apparent when they use a surname which could refer to many different people, though rare surnames or the names of foreign battles may be more distinguishable. The names of prominent town centre streets and squares, which are used by many people, have a much higher profile than those of residential streets and back roads. These may have been named quite casually, without fully appreciating that a name might have associations with a contested figure. On occasion, whole settlements can be named after individuals, although this is rare in Wales. Local Authorities are responsible for street name and numbering and are subject to statutory requirements.

1.2.3: building names

Building names for premises owned by public bodies or charitable organisations imply that the person commemorated is being honoured in some way. The most prominent examples include schools, university buildings, public halls, community buildings and public offices. As the name is often given in full, the identity of the person is usually clear. In many cases, a plaque or information panel is also presented. Naming of educational institutions is especially sensitive because of the impact on young people.

1.2.4: pub names

Although pubs are not publicly owned, they have a special prominence as buildings in public view. In many cases the origins of their names are obscure. Even when individuals are commemorated it can be hard to tell whether the name refers to a landed family or long-established title rather than a particular individual.

1.2.5: statues and sculptures

Statues especially may be loaded with unspoken values. Traditionally, the ‘man on a pedestal’ was idealised in the classical manner and his formal dress or associated props delivered a particular message about his achievements or status. Equestrian statues, with the subject set high on a horse, further elevated the person commemorated above the ‘common people’. While the sponsors of statues may have wanted to give their subjects the ultimate respect, this can be offensive to people today who see them in a different light; for example, as aggressors who conquered peoples to expand the British Empire or industrialists who endangered and exploited their workers. Some more recent designers have taken non-traditional approaches to their subjects, aiming to bring out their individuality rather than idealise them. For example, the statue of Betty Campbell in Cardiff honours its subject but does not idealise her.

The form of commemorations may raise particular issues for some cultural groups in Wales. For example, the portrayal of human figures is forbidden by Islam and some Jewish and Christian traditions. It is important to be aware of such views when making choices between statues, non-figurative sculptures, plaques or other forms of commemoration.

Sculptures other than statues may commemorate people or events in more subtle and ambiguous ways. Using symbols or abstraction can present narratives or ideas for audiences to interpret. They can offer more balanced or informative commemorations than conventional statues.

1.2.6: paintings in public places

While most painted portraits are privately owned or in museums, some should be considered as public commemorations because they hang in public places such as court rooms or council chambers. Artists may interpret people and events in subtle and sensitive ways, but some paintings have proved contentious. Formal portraits of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries often used the same idealising approach as traditional statues; for example, showing soldiers proudly in their uniforms or politicians in robes of office. Paintings to commemorate events may also have oversimplified the past.

Values may be communicated through the type and style of commemoration as well as the subject. This is relevant both when considering actions to address existing commemorations and mitigate any damaging impacts, and when considering new forms of commemoration

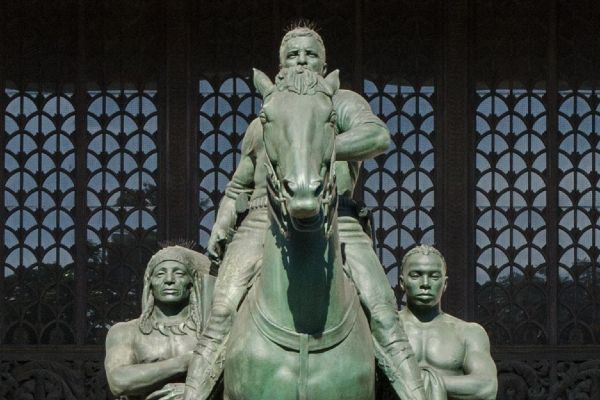

Case study: Teddy Roosevelt statue, New York

Theodore Roosevelt is a generally well-regarded former president of the United States who held office between 1901 and 1909. Nevertheless, his statue of 1939 outside the Natural History Museum in New York was removed in 2022. This was not because of who was commemorated but he was represented. Roosevelt was depicted on horseback flanked by an African and a Native American who appeared subservient to him. The sculptor, James Earle Fraser, described the work as a ‘heroic group’ and explained the two accompanying figures as:

… guides symbolizing the continents of Africa and America, and if you choose may stand for Roosevelt's friendliness to all races.

In the context of the museum, however, this imagery evoked so-called ‘scientific racism’ and historian James Loewen described it in 1999 as ‘a declaration of white supremacy.’ The earliest protests against the statue by native Americans were in 1971. African Americans also judged that it presented them as ‘primitive’ and in a hierarchy below the ‘civilized’ white man. In 2021, New York’s Public Design Commission voted unanimously to remove the statue, which is to be redisplayed with interpretation at Roosevelt’s Presidential Library in North Dakota.

1.3: location

Location is a key factor in the impact of a commemoration. For example, siting a plaque to mark where someone was born or erecting a monument where an event took place may be seen as highlighting a historical fact rather than celebrating the person or the occasion. A commemoration of the same subject in a less relevant location or in a community where the subject was controversial might not seem as neutral.

Prominent statues in particular can be provocative, especially in city centres where they are seen more often. Some were deliberately positioned to assert the authority of one family or group over a place. In other words, the statue can be seen to say ‘this place belongs to us’ rather than ‘this place is for everyone’. Public spaces, such as town squares, or places that should treat everyone fairly and equally, such as law courts or town halls, are more sensitive locations than semi-private ones, such as the frontages of offices. A monument in a place explicitly devoted to honouring people, such as a ‘hall of heroes’, may be seen to give society’s unanimous approval to those commemorated unless there is accompanying interpretation to explain the monument and how perceptions may have changed since it was created.

To note:

- The impact of location is an important factor, both when considering actions to address existing commemorations and when considering proposals for new ones.

Case study: the locations of statues of Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher was a historically important figure, but people find it hard to view her objectively. As prime minister, between 1979 and 1990, she was both idolised and detested. She presided over unemployment and industrial strife, including a deeply divisive miners’ strike. Nevertheless, she was Britain’s first female prime minister; she won three general elections, she led the country during the Falklands Conflict and she was recognised worldwide as the ‘Iron Lady’.

Statues of Margaret Thatcher were planned soon after she left office but have proved difficult to site. One was decapitated in a gallery in 2002 and the temporary display of a large image of her in the Senedd in 2008 was strongly criticised and called ‘an insult to the people of Wales’. In 2017, Douglas Jennings completed a statue for Parliament Square but Westminster Council refused permission on several grounds, including the costs of policing. This has now been installed in her hometown of Grantham, where a consultation indicated it would be relatively uncontentious, though it was pelted with eggs soon after its unveiling.

There are, however, two statues of Margaret Thatcher in apparently suitable venues: the Members’ Lobby of the House of Commons and on the Falkland Islands.

1.4: perspective, the importance of hindsight and evidence

The understanding of people and events may change in hindsight or when new information comes to light. Decisions about whether to commemorate them can appear misjudged a few years later. Many local authorities and institutions have a rule that individuals cannot be considered for commemoration until at least 10 years after their deaths. Nevertheless, there can be pressure to act sooner, particularly following a high-profile disaster or if a popular figure dies unexpectedly.

Jimmy Savile is one of the clearest examples of the risks of commemorating people prematurely. Evidence that he abused vulnerable adults and children became widely known soon after he died, but by that time a Glasgow swimming pool was displaying a statue of him and a plaque had been put on his house in Scarborough, calling him an ‘entertainer and philanthropist’. Both were taken down within months.

Much longer periods may be required for the historical significance of people or events to be understood by researchers or appreciated by a wider public. For example, the failure until recently to acknowledge the sacrifices made by soldiers from British colonies in south Asia, Africa and the Caribbean in two world wars. These soldiers were neither depicted nor named on British war memorials until decades after their white comrades, alongside whom they fought.

To note:

- Unexpected challenges are more likely if commemorations are not informed by accurate historical information and ‘due diligence’.

- Events and people’s actions have both short-term and long-term effects so that perceptions of commemorations can change dramatically over time.

Case study: Statue of a Girl for Peace, Seoul

The 'Pyeonghwaui sonyeosang' (평화의 소녀상, English: 'Statue of a Girl for Peace') bronze sculpture depicts a seated teenage girl in traditional Korean clothing with clenched fists. There is an empty chair next to her and a small bird is sat on her shoulder. On the ground behind her there is a representation of the shadow of a bent-backed older woman. The original sculpture in Seoul, South Korea, is located opposite the main entrance to the Japanese embassy. It was unveiled in 2011 by the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan.

From around 1932, during the Japanese wars of expansion, the Imperial Army worked with local agents to develop a network of military brothels. By the time Japan surrendered at the end of World War II, around 200,000 enslaved women had been trafficked into these ‘comfort stations’, most of them from Korea, which had been annexed by Japan in 1910. The fate of the so-called ‘comfort women’ was a taboo subject for decades but, with the democratisation of South Korea in the 1980s, it became possible to discuss the topic in print. This led to growing calls for Japan to apologise and compensate the now elderly survivors.

An agreement was brokered in 2015 that would see Japan pay a large sum and acknowledge the direct involvement of the Japanese military in the brothels, but this was conditional on the removal of the 'Statue of a Girl for Peace'. The deal fell apart when a replica of the statue appeared near Japan’s consulate in Busan. Korean authorities have sought to remove both statues several times but have been prevented by protesters. Near replicas of the statue have also been commissioned by Korean expatriate communities in Germany, Australia and the USA. Although these replicas have been placed in public parks rather than near Japanese government offices, several in the USA have caused tension between local Korean and Japanese communities.